What’s the Issue?

In this part II of my post on the IPCC report I’d like to look at the positive aspects of the report – that is, the ways we can help limit global warming below at least 2°C by a wholesale change in behaviours, attitudes, practices, and a mindset that is better coupled to the human-nature connection. A decoupling of this connection is what has ultimately led to the changes found in the report including a 1.1°C temperature rise since 1850-1900 from CO2 emissions.

It’s easy to become overwhelmed by the inactions of governments on climate change, which can lead to eco-paralysis and the inability to act, so in this post I’d like to focus on what individuals and communities can do and the power we have to drive change. I’m not saying that individuals are wholly responsible for slowing climate change, but I am saying that everyone has a part to play.

Climate change is an ecological, scientific and technological issue; but it is also a social, political and cultural one, and tackling it will involve social, political and cultural changes that need Joe Bloggs as much as the highest levels of government.

Let’s stay solutions-focussed!

This will mean looking to alternative ways of limiting our impacts on the environment, which will include changing attitudes, mindsets, behaviours and practices.

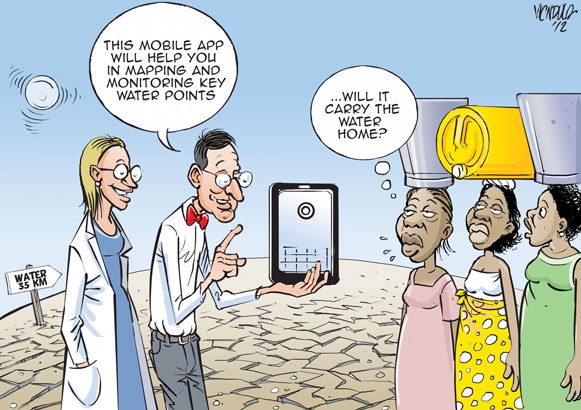

The most detrimental “solution” is the one that believes that we can tackle the changes needed using the same tools we have always used.

We can change behaviours and attitudes about our place on the planet by recalibrating our understandings of our connection to nature. Humans are part of nature, not superior to it. Indigenous knowledges of the role of nature in human society and vice-versa were instrumental in the ways in which people lived for millennia before industrial activities. In recent times, activists and policymakers alike have pointed to the need to return to Indigenous knowledge in environmental management and social policies.

Ideas like Buen Vivir (among similar traditional and Indigenous concepts and philosophies) recentre Indigenous approaches to the environment and community, thereby making them potential solutions for changing the way we live and organise society, globally. By changing this aspect of society, not only in how we act and the choices we make on a daily basis, but also in the policies that governments adopt, we can lessen our usage of natural resources and thus impacts on the natural environment.

However, we have one big global problem: political inaction. So rather than waiting for policies to change, we can start to do our part in slowing the changes to climate. How? It starts with a change in the way we think, followed by a change in the way we live.

The Indigenous Kichwa Peoples of the Andes in South America call this change in mindset and practices Vivir Bien. If you’re familiar with Buen Vivir, you will know that Buen Vivir is the big picture idea of what sustainability and wellbeing should look like. It involves not only environmental sustainability, but also the social wellbeing of communities (not just competitive individuals), which in many ways is connected to the ways we value the environment. So, environmental and social wellbeing are inherently connected to each other in an idea I call Socio-Eco Wellbeing.

Vivir Bien is the same idea, based on the same principles as Buen Vivir, only it is described as how it manifests in daily living. The full matrix of principles can be found in my book. There are many examples on the internet about daily actions individuals can take to tackle climate change such as:

- contacting leaders

- adopting a climate friendly diet

- limiting our resource use

- switching to renewable sources where possible

- consuming less, and

- using your vote wisely.

These are great micro ideas that make important changes, but they also need to be backed up with the right mindset. That is, a switch to communal thinking and away from individualism, and; a consideration of the reciprocal human-nature connection in every action and decision taken. This also calls for macro ‘big picture’ thinking.

Here is an excerpt from my book on some of the (non-exhaustive) ways in which communities can implement the principles in their daily lives:

•• Adopting a reciprocal approach to our relationship with nature;

•• Public participation and enabling decision-making in a manner that honours

that reciprocity;

•• Fostering solidarity and harmony through an environment of community;

•• Ensuring equity in participation in public decision-making;

•• Manifesting a responsibility to participate in decision-making;

•• Educating future generations;

•• Participating in economic life;

•• Understanding their fundamental rights and responsibilities, including those

of the environment;

•• Exercising those rights;

•• Promoting and protecting cultural values and practices;

•• Valuing the role of health in a community.

Adding to that is the reducing consumerism and the material vision of the environment as a commodity – a consequence of adopting a reciprocal relationship to nature in our decision-making and behaviours.

These changes combined can help empower individuals and communities to do their part in limiting environmental impacts and therefore slowing climate change. Inevitably, the changes flow up.

In the words of the Dalai Lama, “If you think you’re too small to make a difference, try sleeping with a mosquito.”

More reading:

Buen Vivir as an Alternative to Sustainable Development: Lessons from Ecuador, Routledge, 2020

How to Live the Good Life, Sustain the Mag